The Islamic Urban Setting: Countering Western Fallacies

Lombard notes that Sao

Paulo in Brazil, said to be the fastest growing city in the

world (its population rising from 60,000 in 1888 to 2 million in

1950), hardly, in fact, compares with the growth of Baghdad

from 500 inhabitants in 762 to

nearly 2 million in 800.[1]

This was by no means an isolated case. Some of the greatest

cities of the Middle Ages anywhere were all founded in early

Islam, cities such as

Cities played a fundamental part in the history of

Islam, which is somehow paradoxical when remembering that those

who carried the faith throughout the world, from the Himalayas

to the Pyrenees, were mainly Arabs and Bedouins ‘who never slept

between four walls,’ says Marcais.[11] A point also noted by

Udovitch, who contrasts the desert and oases ‘the setting of its

birth,’ with the cities and towns ‘the setting of Islam's growth

and maturity.’[12] From Makkah

and Madinah

, the centres of power, culture, and wealth moved to such urban sites as

Even when acknowledging the urban character of

Islamic civilisation, mainstream Western historians and

commentators wrote very disparagingly on Islamic cities,

writing, which is, however, wholly contradicted by historical

reality. Three main strands of attacks on Islamic cities, and

their refutation, are dealt with here.

The first attack on Islamic cities is that they were

not cities in the modern sense. Max Weber, in the late 19th

century, for instance, suggested that there were five

distinguishing marks of the medieval city: fortification;

markets; a legal and administrative system; distinctive urban

forms of

association, and partial autonomy.[16] Since the Muslim city

lacked some of these marks, Weber maintained, they were not

cities, just chaotic concentrations of crowds.[17]

Weber’s, like others’, derogatory approach to the

Islamic city is not unique. Each and every aspect of Islamic

civilisation, sciences, history and faith, has been identified

and defined from a derogatory angle. This work will show this

recurrently. A few instances are looked at here, briefly, to

illustrate this, before refuting Weber and his hordes of

followers. Muslim universities are thus said not be

universities, because they lacked a definite date and legal

status in their foundation.[18] Which is odd

considering that neither were subsequent European universities,

which were also based in every respect (organisation,

administration, campus system, certificates, learning…) on

Muslim antecedents.[19] The same is also said

about Muslim chemistry, defined as an occult practice called

alchemy, which is also odd when Western chemistry inherited

everything (classification of metals, the use of

experimentation, the vocabulary, the laboratory etc,) from its

Islamic predecessor.[20] And the same with

respect to the observatory in Islam, which is deemed not an

observatory, when every single feature found in the Muslim

observatory (use of large instruments, gathering of large number

of scientists, prolonged observation, etc,) was to be found in

its successor the Western observatory.[21] And the same is said

and written with respect to hospitals, described as mere

‘maristans.’ Muslim civilisation, itself, is said to be a

plagiarised form of Greek civilisation, whilst the faith of

Islam, said to be a mere corruption of other faiths.[22] Even the military

victories of Muslim armies, including that of Ain Jalut in 1260

which broke the deadly Mongol onslaught on Islam, was painted as

a pale success against a handful of Mongols,[23] or was only a skirmish

says Saunders,[24] who oddly enough also

says that it was a turning point in history, and that the Mamluk

victory at Ain Jalut saved Islam.[25] Hence, Weber’s

derogatory attitude to Islamic cities is neither new, nor

unique. Nor can it stand up to scrutiny, as shown by the

following.

In contrast to the ancient city or to the Western

communes of the later Middle Ages, Islamic cities possessed no

special legal or corporate status. The town as such is not

recognized in Islamic law notes Udovitch.[26]

Nor can we identify any institutions for internal governance,

such as guilds or municipal councils, which have been used by

social historians to deny the title of city to the Islamic city.

But as Goitein points out, "the medieval Islamic city was a

place where one lived, not a corporation to which one belonged."[27]

The 'ulama', or religious scholars, Udovitch notes, ‘served as a

cohesive force within the urban amalgam,’ just as did the

muhtasib (the state inspector of corporations, trades, and

markets) and a number of formal and informal groupings,

including the extended families, the neighbourhoods, local

constabulary, and religious orders. The Islamic cities

represented effective social realities, and as seats of the

government or its representatives they guaranteed security; as

local markets or international emporiums they provided economic

opportunities; and with ‘their mosques and madrasas, their

churches, synagogues, and schools, their bathhouses and other

amenities, they contained all that was needed for leading a

religious and cultured life.’[28] Oldenbourg also notes

how in large cities there were schools for all, free for young

children and sometimes even for university students; there were

public baths at every street corner, as well as many private

pools.[29] Oldenbourg also points

out that Muslim cities, cosmopolitan by nature, were great

centres of commerce, into which caravans flowed from all corners

of the East and the West.[30]

They were administrative centres employing thousands of clerks,

cultural centres where sometimes tens of thousands of

manuscripts were preserved in public and private libraries,

where schools of literature and philosophy of all persuasions

met, where men assembled in public squares to discuss the

Qur’an; each of these cities a world in miniature; even the

small cities, like Homs and Shaizar, had ‘an opulence and

comfort which European kings might have envied.’[31]

Islamic cities thus met the requirements of the modern city we

have today, and were centuries ahead of their Western

counterparts in doing so.

The second form of attack against Islamic cities

is their ‘chaotic’ nature, the chaos seen as a child of

Islam, the faith. Thus, Planhol says:

‘Irregularity and anarchy seem to be the most striking qualities

of Islamic cities. The effect of Islam is essentially negative.

It substitutes for a solid unified collectivity, a shifting and

inorganic assemblage of districts; it walls off and divides up

the face of the city. By a truly remarkable paradox this

religion that inculcates an ideal of city life leads directly to

a negation of urban order.’[32]

This is part of a wider line of attack on Islamic

cities as outlined by AlSayyad:

‘Housing is mainly made up of inward oriented core residential

quarters, each allocated to a particular group of residents and

each is served by a single dead end street. As for its spatial

structure, the Muslim city has no large open public spaces and

the spaces serving its movement and traffic network are narrow,

irregular and disorganised paths that do not seem to represent

any specific spatial conception.’[33]

The anarchy attributed to the Islamic model is

refuted by historical evidence, though. Jairazbhoy, for

instance, argues:

‘First

of all irregularity has always been alien to Islamic art, and

indeed in architectural designs there is usually an over zealous

desire for symmetry. The irregularities of streets in Muslim

towns are the result of subsequent haphazard growth…. It is

people who are at fault, not the system.’[34]

The image conveyed in Western scholarship of Islam as

a faith being the source of anarchy and asymmetry is, indeed,

fundamentally contradicted by the faith. Gazing at designs on a

Muslim prayer carpet, whether these designs are of Makkah

, or a mosque interior, or any other motif, will show absolute, perfect

symmetry and precision. Anything on the left side of the carpet

is found on the other as if computer designed. No Islamic carpet

will show asymmetry. Prayer itself, in a mosque (or anywhere

else), is perfect order, in the reading of the verses, in the

timing of the prayers, in the direction of the prayers, in the

numbers of the (rakaas) (prostrations); in the line of

worshippers, in the simultaneity and harmony of their

prostration etc. The Qur’an is recited with absolute, perfect

orderliness, in form, in sound, in the repetitions, in the

length of the verses, etc.. Exactitude and utmost precision are

constantly expected of the faithful in every deed, in making

contracts, in inheritance matters, in the way of fasting, in

distributing alms, in the way of performing pilgrimage etc. The

gardens of Islam are absolute perfect symmetry and order; and so

is the art of Islam, as the consultation of any book on Islamic

art will show, and so on. It is secular, Western inspired,

Islamic society, which is messy. Such ‘modern’ society simply

has no parameter upon which to build order. Neither has it any

parameter of any sort that helps it build or respect green

spaces, or look adequately after its water supply, or clean its

streets etc. The chaos of modern Islamic cities today is,

indeed, undeniable, but, rather than being the outcome of Islam,

it is the result of the secular elites in power, and their

ineptness in imitating Western models, whilst they have only

contempt for anything Islamic.

Historically speaking, Al-Sayyad demonstrates that

the irregularity of forms in Muslim cities as a response to

social and legal codes and as a representation of the Islamic

cultural system had no foundation. Muslim towns were originally

designed according to very regular geometric patterns, and they

only achieved an irregular form in later years probably due to

many factors.[35]

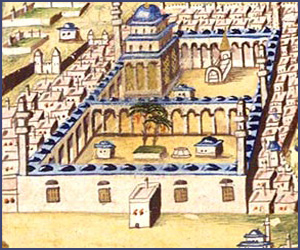

In this respect, the outline by Lassner on the foundation of

Samarra (today’s Iraq

) in the 9th century is an excellent illustration of how

fundamentally Islamic urban design stands wholly at the opposite

end of what stereotypes claim. Samarra, the second great capital

of the Abbasid caliphate, was situated along the Tigris some

sixty miles (ninety-seven kilometres) north of Baghdad

. The city was subject to meticulous planning; several thoroughfares

running almost the entire length and breadth of the city.[36] The main thoroughfare

was the "Great Road" (shari' al-a'zam), called al-Sarjah,

extended the entire length of the city. With later extensions it

ran some 20 miles (32 kilometres) and was reported to have been

300 feet (91 meters) wide at one point. The part of the road

that still exists, although somewhat narrower (240 feet or 73

meters), testifies, indeed, to dimensions that were staggering.

The great government buildings, the Friday mosque and the city

markets were all situated along al-Sarjah; and it was throughout

the entire history of the city the main line from which most of

the city's traffic radiated toward the Tigris and inland.[37] The market areas were

subsequently enlarged and the port facilities expanded as part

of an energetic program that included the refurbishing and

strengthening of already existing structures.[38] The new mosque was an

enormous structure; and as it was to serve the entire population

of Samarra (which resided for the most part along the first two

thoroughfares inland), three major traffic areas had to be

constructed along the width of the urban area. Each artery was

reported to have been about 150 feet (46 meters) wide so as to

handle the enormous traffic; each artery flanked by rows of

shops, representing all sorts of commercial and artisanal

establishments; the arteries in turn connected to ample side

streets containing the residences of the general populace. The

Great thoroughfare was extended from the outer limits of

Samarra, and feeder channels that brought drinking water flanked

both sides of the road.[39] And Samarra was not

alone. Sketches of all the cities founded under Islam (Fes

, Al-Qayrawan

, Cairo

…) equally had wide roads and spaces, green spaces, and perfect geometry

and symmetry were fundamental to their design.

In fact, still in relation to urban chaos and

anarchy, if a brief comparative exercise between Islamic and

Western cities during the medieval period (and even up to the

recent times) is made, it will further confirm how, in general,

Western writing is the very opposite of historical reality.

Islamic cities, first, like large Islamic towns, were paved with

stones, and were cleaned, policed, and illuminated at night,

whilst water was brought to the public squares and to many of

the houses by conduits.[40] The houses were large

buildings, several storeys high, housing numerous families, with

terraces on the roofs, internal galleries and balconies, and

fountains in the centre of the courtyards.[41]

10th century Cordova is said to have had 200,000

houses, 600 mosques, and 900 public baths, and its

thoroughfares, for a distance of miles, were brilliantly

illuminated, substantially paved, kept in excellent repair,

regularly patrolled by guardians of the peace.[42] Living conditions in

16th century Algiers

, according to Western contemporary visitors:

‘Compared favourably with those in northern capitals. The

domestic architecture, the flowered patios and gardens of the

race which built the Alhambra were among the most attractive in

the world. Every respectable house had a galleried courtyard and

a flat roof embellished with potted plants. An efficient water

supply provided numerous fountains and cleaned the streets to a

degree unknown in England.’[43]

And long would be the list of early Islamic cities

which could boast huge expanses of gardens.[44]

Every city had its countless gardens, and on the outskirts were

great orchards full of orange and lemon trees, apples,

pomegranates, and cherries.[45]

In North Africa

, one learns of a multitude of gardens, surrounding and inside cities

such as Tunis

, Algiers

, Tlemcen, and Marrakech

.[46]

In the city of Samarra, a garden of the 9th century

consisted of 432 acres, 172 of which being gardens with

pavilions, halls and basins.[47]

In Turkey, Ettinghausen says: ‘devotion, if not mania’ for

pretty flowers was prevalent everywhere.[48]

Al-Fustat, in Cairo

, with its multi-storey dwellings, had thousands of private gardens,

some of great splendour.[49]

In contrast, Western Europe could not compare on any

front with the Muslim East.[50] Compared to Baghdad

, Paris, Mainz, London and Milan were not even like modern provincial

cities compared to a capital. ‘They were little better than

African villages or townships, where only the churches and the

occasionally princely residence bore witness that this was an

important centre.’[51] The streets of both

Paris and London were receptacles of filth, and often

impassable; at all times dominated by outlaws; the source of

every disease, the scene of every crime.[52] The mortality of the

plague was a convincing proof of the unsanitary conditions that

everywhere prevailed; the supply of water derived from the

polluted river or from wells reeking with contamination.[53] Medieval Muslim

visitors to Christian towns complained-as Christian visitors now

to Muslim towns do of the filth and smell of the "infidel

cities."[54] At Cambridge, now so

beautiful and clean, sewage and offal ran along open gutters in

the streets, and "gave out an abominable stench, so . . . that

many masters and scholars fell sick thereof."[55] In the thirteenth

century some cities had aqueducts, sewers, and public latrines;

in most cities rain was relied upon to carry away refuse; the

pollution of wells made typhoid cases numerous; and the water

used for baking and brewing was usually-north of the Alps-drawn

from the same streams that received the sewage of the towns.[56]

Italy was more advanced, largely through its Roman legacy, and

through the enlightened legislation of Frederick II for refuse

disposal; but malarial infection from surrounding swamps made

Rome unhealthy, killed many dignitaries and visitors, and

occasionally saved the city from hostile armies that succumbed

to fever amid their victories.[57]

A third, and final, stereotype about the Islamic

city, as already noted above, is with regard to the segregation

of races and ethnic groups. This again has no hold in reality.

There has never been in Islam anything of the segregation

approaching the American southern states, or South African

apartheid system, or in most modern Western agglomerations

today. Islam is not segregationist either as a faith or society.[58]

Van Ess observes that there

were no ghettos in the Islamic world all the way down to modern

times. Members of the same religious community often lived in

the same quarter for reasons of family solidarity; but they were

not kept apart from Muslims deliberately and on principle. In

particular, they were not unclean; they could be invited to

dinner.[59]

Throughout the Muslim world, whether under the Arabs, or the

Turks

, all ethnic groups and faiths, had access on equal terms to

every single amenity or service,

and they formed part of the Islamic whole, and shared in

opportunities, and even at the highest echelons of power.[60]

The Jews in Cairo

, for instance, are mentioned as practicing the professions of medical

doctors, artisans, accountants, and despite professional

specialisation, there is no instance of segregation of

populations on ethnic or lines of faith with regard to

professions and trades.[61] The same was true in

Cordova, where under Islam, there is no evidence of a

segregation of the Jewish population from its Islamic

counterpart.[62] There is in fact

plenty of evidence showing quite the reverse, a dense

intermingling of faiths, which also includes the mozarabs

(Spanish Christians living under Muslim rule).[63]

In fact, segregation in that city followed precisely the

Christian taking of the city in 1236. As soon as the city

was taken by the Castilian, one of their first measures

was to remove both Muslim and Jewish populations, who were then

forced to re-locate into isolated neighbourhoods, cut off from

access to every form of land communication.[64]

In the instance when the Islamic state intervened to allocate

one particular place in a city to a particular group, this was

based on the need to guarantee a right of space to a group of

people who had lost their worldly rights and possessions

elsewhere. For instance, when Al-Hakam I of Spain (r. 796-820)

banished the Cordovans in the early 9th century, they

were offered a part of Fes

to resettle.[65]

The same happened with the Jews, who when banished by the

Spaniards in 1492 found exactly the same space and rights in the

Ottoman urban realm.[66]

And they were not just settled in the new space, their social

status rose, too. The startling rise of the new port of Algiers

was largely due to the influx of

Aragon Jews, even if the port itself was established by

Kheir-Eddin Barbarosa (early 16th century).[67] They achieved

extraordinary pre-eminence in Morocco

, too, during the 16th century.[68] And the same happened

with the Muslims who were banished from Spain in 1609-10 and who

were allocated parts of towns and cities, farming lands, trades

and businesses from Morocco through Algeria to as far as Turkey

and Syria

.[69]

At all times, indeed, the Islamic city offered an

image of a vast gathering of multiple faiths and races. Early

Basra

, for instance, had a substantial population of Hindus, Yemenis,

Persians and Arabs.[70]

Muslim Palermo

in Sicily

included Greeks,

Lombards, Jews, Slavs, Berbers

, Persians, Tatars and

Black Africans.[71]

The monk Theodosius, brought from Syracuse with Archbishop

Sophronius in 883, acknowledged the grandeur of the new capital,

describing it as:

"Full

of citizens and strangers, so that there seems to be collected

there all the Saracen folk from East to West and from North to

South... Blended with the Sicilians, the Greeks, the Lombards

and the Jews, there are Arabs, Berbers

, Persians, Tartars, Negroes, some wrapped in long robes and turbans,

some clad in skins and some half naked; faces oval, square, or

round, of every complexion and profile, beards and hair of every

variety of colour or cut."

[72]

And these were no exceptional

cases, as Watson points out.[73]

What was true of Palermo

in the 9th century was

true of Algiers

in the 17th; a city

Lloyd says, which was not just clean and well disciplined, but

also every visitor remarking on the law and order that prevailed

in a city inhabited by persons of every nationality and

religion.[74]

The public baths of the

city, Fisher notes, were made available to persons of all races

and creeds, and even to slaves.[75]

Islamic buildings, too, in their design, just like

the towns, cities and society, betrayed the same cosmopolitan

spirit, as Durant notes:

‘From

the Alhambra in Spain to the Taj Mahal in India

,’ Islamic art overrode all limits of place and time, and ‘laughed at

distinction of race and blood.’[76]

[1]

Ibid; p. 118.

[2]

A.L. Udovitch: Urbanism; in The Dictionary of the

Middle Ages;

op cit; Vol 12; pp 306-10.

[3]

M. Lombard: The Golden; op cit; p. 123.

[4]

E.E. Herzfeld: Geschichte der Stadt

[5] M. Clerget: Le Caire (Cairo

1934), pp. 126; 238-9;

J. Abu Lughod:

[6]

Al-Maqqari: Nafh Al-Tib. Translated by P.De

Gayangos: The

History of the Mohammedan Dynasties in Spain

(extracted from Nifh Al-Tib by al-Maqqari); 2 vols (The Oriental

Translation Fund;

London, 1840-3), Vol 1; p. 87.

[7]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit; vol 1;

pp 613-4.

[8]

M. Acien Almansa and A. Vallejo Triano: Cordoue, In

Grandes Villes Mediterraneenes du Monde Musulman

Medieval; J.C. Garcin editor (Ecole Francaise de

Rome; 2000), pp .117-34;

p. 117.

[9]

A.M. Watson: A Medieval Green Revolution; New Crops and

Farming Techniques in The Early Islamic World, in The

Islamic Middle East 700-1900; edited by A. Udovitch

(Princeton; 1981), pp. 29-58; note 45; p. 57.

[10] M. Acien Alamnsa and A. Vallejo Triano: Cordoue; op cit; p. 117.

[11] G. Marcais: l’Urbanisme Musulman, in Melanges d’Histoire et

d’Archeologie de l’Occident Musulman; Vol 1;

Gouvernement General de l’Algerie; Alger; 1957; pp

219-31; at p. 219.

[12]

A.L. Udovitch: Urbanism; op cit.

[13] Ibid.

[14] G. Marcais: l’Urbanisme; op cit; p. 219.

[15]

T. Glick: Islamic and Christian; op cit; p. 114.

[16]

M. Weber: The City; D. Marindale and G. Newirth

tr. (Glenco; 1958).

[17]

in N. AlSayyad: Cities and Caliphs (Greenwood

Press; London; 1991), p. 34.

[18]

H. Rashdall: The Universities

of Europe in The Middle Ages,

ed F.M Powicke and A.G. Emden, 3 Vols (Oxford University

Press, 1936).

[19]

J. Ribera:

Dissertaciones y opusculos, 2 vols (Madrid, 1928).

George Makdisi:

The Rise of Humanism in Classical Islam and the

Christian West (Edinburgh University Press, 1990).

[20]

E.J. Holmyard:

Makers of Chemistry (Oxford at the Clarendon Press,

1931).

[21] L. Sedillot: Memoire sur les instruments astronomique des Arabes,

Memoires de

l’Academie Royale des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres de

l’Institut de France 1: 1-229 (Reprinted Frankfurt,

1985).

A. Sayili: The

Observatory

in Islam

(Turkish

Historical

Society, Ankara, 1960).

[22]

Such as found in literally every work on Islam, such as:

-C. Brockelmann: History of the Islamic Peoples;

tr. from German (Routledge and Kegan Paul; London; 1950

reprint).

[23]

G. Guzman: Christian Europe and Mongol

[24]

J.J. Saunders: The History of the Mongol Conquests

(Routlege & Kegan Paul; London; 1971), p. 117.

[25]

J.J. Saunders: Aspects of the Crusades;

[26]

A.L. Udovitch: Urbanism; op cit; p. 310.

[27]

D. Goitein: A Mediterranean

Society in A.L.

Udovitch: Urbanism; pp. 310-1.

[28]

A.L. Udovitch: Urbanism; pp. 310-1.

[29]

Z. Oldenbourg: The Crusades; pp. 497-8.

[30]

Ibid; p. 498.

[31]

Ibid.

[32]

Xavier de Planhol: World of Islam (Ithaca; Cornell

University Press; 1959), p. 23. in N.AlSayyad: Cities;

op cit p. 23.

[33]

N.AlSayyad: Cities; p. 6.

[34]

R. Jairazbhoy: Art and Cities of Islam (New York

Asia Publishing House; 1965), pp 59-60, in AlSayyad p.

23.

[35]

AlSayyad:

Cities; p. 154.

[36]

J. Lassner:

[37]

Ibid.

[38]

Ibid.

[39]

Ibid; pp. 643.

[40]

F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; pp 148-50.

[41]

Z. Oldenbourg: The Crusades; op cit; p. 476.

[42]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit; Vol 3;

pp 520-2.

[43]

In C. Lloyd: English Corsairs on the

[44]

A.M. Watson: Agricultural Innovation in the Early Islamic World

(Cambridge University Press; 1983), p.117.

[45]

Z. Oldenbourg: The Crusades; op cit; p. 476.

[46]

Al-Bakri: Description: 9 ff; Torres Balbas: La Ruinas;

275 ff; G.Marcais: Les Jardins de l’Islam;

all in A. Watson: Agricultural Innovation;

op cit; p. 118.

[47]

R. Ettinghausen: Introduction; in The Islamic Garden,

Ed by E.B. MacDougall and R. Ettinghausen (Dumbarton

Oaks; Washington; 1976), p. 3.

[48]

Ibid; p.5.

[49]

G. Wiet:

[50]

Z. Oldenbourg: The Crusades; op cit; p. 497.

[51]

Ibid.

[52]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit; Vol 3; pp 520-2.

[53]

Ibid.

[54]

Munro and Sellery; p. 266 in W. Durant: The Age of

Faith; op cit; p. 1003.

[55]

In Coulton: Panorama; 304 in W. Durant: The Age of

Faith; op cit; p. 1003.

[56]

[57]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p. 1003.

[58]

I.e: G. E.

Von Grunebaum: Medieval Islam; op cit; p. 177 and p.210.

F. Artz: The Mind; op cit; p.137. Joseph Van Ess:

Islamic Perspectives, in H. Kung et. al: Christianity

and the World Religions (Doubleday; London, 1986),

p.80.

[59] J Van Ess: Islamic Perspectives: op cit; p.104.

[60] Y Courbage, P Fargues: Chretiens et Juifs dans l'Islam Arabe et Turc

(Payot, Paris, 1997), T.W. Arnold: The Preaching of

Islam (Archibald Constable, Westminster, 1896);

R. Garaudy:

Comment l'Homme devint Humain (Editions J.A, 1978),

p.197.

[61] D. Behrens Abouseif; S. Denoix, J.C. Garcin: Cairo

: in Grandes Villes; op cit; pp. 177-203;

p. 185.

[62]

M. Acien Almansa and A. Vallejo Triano: Cordoue; op cit;

p. 124.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid; p. 118.

[65] E. Levi Provencal: La Fondation de Fes

; in Islam d’Occident (Librairie Orientale et Americaine; Paris;

1948), pp. 1-32.

[66] Y. Courbage, P. Fargues: Chretiens et Juifs; op cit.

[67]

G. Fisher:

[68] H.de Castries: Une Description du Maroc sous le regne de Moulay Ahmed

al-Mansour; 1596 (Paris; 1909), pp. 119-20.

[69]

K. Brown: An urban View of Moroccan History;

[70] N.L. Leclerc: Histoire de la medicine Arabe. 2

vols (Paris, 1876), vol ii, pp 279-82.

[71]

Al-Maqqari Nafh al-Tib, ed. Muhammad M. Abd

al-Hamid. 10 vols (

[72]

In C. Waern: Medieval

[73]

A.M. Watson: Agricultural; op cit; p 92.

[74]

C. Lloyd: English Corsairs on the

[75]

G. Fisher:

[76]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; pp.270-1. |